The classic era of cinema design was the 1930’s. During this decade, Art Deco imported from Continental Europe and the United States was the preferred style. Theaters embraced this decorative modernism, becoming subtle symbols of a modern, independent India. On one end of Marine Drive the Regal was showing the great Indian myth-building epics of early Hindi cinema, while on the other end Gandhi was finalizing his self-rule and resistance doctrines. A succession of ever more sexy theaters opened from 1933 to 1938 in the most opulent period of building: The Regal, The Plaza, The Central, The New Empire, The Broadway, and culminating in the 2000 seat Eros across from Churchgate Railway Station. Each featured car parking, elevator lifts, air conditioning, and the latest audio-visual equipment. They were technological marvels covered in streamlined wrappers. Additionally, ground floor retail and housing above would provide supplemental income for the owners, while matching the scale of the neighboring buildings. Openings were not just to watch the movie, they were events with elephants and lights and glamour. Single screen construction continued through the 1960’s, incorporating contemporary fashions in their aesthetics, though tempered by India’s “self-reliance” policies. These later theaters combine a sort of space-age bachelor pad look with the local brand of socialist-realist construction. Notably, the Bombay typology of combining apartments and retail with the theater also continued.

Bombay was the natural backdrop for many films, especially in the post independence era. If the script called for new or modern, they shot Marine Drive; elegance was done at the Taj Motel; lushness was captured in the Oval Maidan; seediness in the backstreets of the cabbies. Films became a sort of propaganda for lifestyle and location, notably the burgeoning metropolis of Bombay. Of course the films were based on and shot in the city, but run through the fantasy factory of filmaking. The city was projected on screens across the nation; it is at least partially responsible for migrants relocating to the mythical city, especially the young runaway boys. Bollywood was a central player in selling the story of a progressive India, and often it took the shape of Bombay.

Bollywood productions are increasingly commodified, no longer reliant on “real” Bombay as a setting. Now most shooting is done abroad or on tightly controlled sets in the north of the city. Also evident is a shift in focus from the dream of a modern India to the dream of an affluent one. The new target audience is the 20 million NRI (Non Resident Indians) living abroad, particularly in London and New York where ticket prices can be ten times that in India and there is more disposable income for associated products. NRI revenue now accounts for 65% of the returns. Marine Drive in Bombay used to be the iconic location of emerging India; argueably it is now any given swanky London night club.

Today single screen theatres are obsolete and closing at an alarming rate. Since 1983, over one third of the 160 or so single screen theaters have shuttered. Multi-screen theaters are increasingly bigger and more diverse to lure patrons that might otherwise watch videos; alternative leisure activities are a requirement to justify the night out: restaurants, stores, bars, cafes, etc. Thus the mall is a more ideal economic location for the theater, where the hermetic environment can capture more revenue than any single activity. Often the movie itself is only a fraction of the overall revenue. Additional tax breaks by the state government compound the trend, as multi-screen cinemas are exempt the otherwise very high entertainment taxes (around 50% of the ticket price). Single screen theaters simply don’t make enough money to thrive, much less renovate. Some have enough nostalgic value (Eros, Liberty) to gain a reprieve, but how long can it last? Unless the theater is full most of the time, it cannot keep up. Thus they tend to play blue chip movies without venturing into more experimental or independent territory. Lacking revenue to renew and refurbish the theater the quality erodes. It might slink into B-movie action/sex films, or just fade into the fabric with shops or squatters taking over the lobby, as in the Strand.

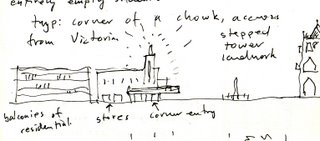

Viewed simply as objects, the theaters are unique in the city for two important reasons: location and shape. First, they occupy a privileged lot in each neighborhood, often associated with a railway station. A typical theater will be located on or near one of the corners of the city’s chowks (major intersections), along with municipal buildings and train stations. Second, they present a large volume of space inside a recognizable landmark. Most theaters have prominent towers above the marquee corner entrance, with shops and apartments that turn the corner and provide a smooth transition to the neighboring fabric. They are simultaneously sensitive and narcissistic. Inside, the auditoriums hold from 800 to 2000 seats with large open spans and typically one balcony; they are wombs away from the teeming streets outside. Today there are often insensitive additions in order to make up for the lost revenue: apartments, offices, and other unidentified boxes that help offset the cost of the movies.

Plans of various cinemas indicating theater (yellow) and apartments (white)

Next stop: Courtyard Cricket