Piece by piece the hippodrome, formerly one of the most monumental buildings in the city at 500 meters long and 120 meters wide, has been broken down into the fragments of park and road that are found today in what is called At Meydanı (Square of Horses). This massive palace of spectacle is relegated to sidebar anecdotes in tour guides. The 30,000 killed in the Nika revolt sounds huge, but the physical presence of the building that brought them together is nowhere to be seen. This massive piece of the city is gone, traced by the shortened roadway and crumbling but still muscular sphendome. Constantine has been emasculated.

Almost everyone in the area is a visitor or serving the visitors. The hippodrome site is pretty close to ground zero for tourism. It is within walking distance to the four most visited places: the Blue Mosque, the Hagia Sophia, the Covered Market, and Topkapı Palace. And yet, the park is curiously vacant. With the July and August sun bearing down during prime tourist season, the few people that are in the At Meydanı are either quickly getting their fill of the monuments, or are clustered in the shade of one of the small trees. It doesn’t have the shade of the courtyard of the Blue Mosque, the fountain of the central garden, or the refreshments of nearby tea gardens. Neither does it have the monumentality of the nearby sites; as such, it is reduced to a curious footnote between bigger and better things.

HIPPODROME: SHAPING THE SUN

In a climate with an abundance of hot sun and cooling breezes it is natural that a tradition of screens and trellises would develop. Pervasive carved window screens did triple duty of keeping prying eyes and the sun out, and allowing air circulation in. They are mostly simple masonry affairs, sturdy and meant to convey security, though often in the palaces they achieve a high degree of fragility that belies their stone origins. This mediation between dark and light is found everywhere from Byzantine churches to the Ottoman baths; these buildings prized shade and darkness as much as light. The threshold between dark and light, inside and outside, was an opportunity to shape the light into the formal mode of that era.

A more quotidian and prevalent form of sun control are the many overhead trellises around the city. Many streets have this form of public covering, negotiating between several different buildings. It usually covers a café, where it is normal to rest at length while playing backgammon and drinking tea. This is one of the most common scenes in Istanbul, whether in Sultanahmet or Zeytinburnu (though in Levent it is more likely you will find umbrellas and a Starbucks). The trellises usually host thick vines, allowing only dappled light to hit the seats below, which die off in the winter time when it is more appropriate to have direct sunlight.

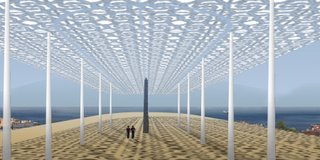

HIPPODROME: TRELLIS MAXIMUS

My proposal is to add a monumental trellis to the former space of the hippodrome, roughly the height and size of the original structure. This would float above the space that is presently broken up by surrounding buildings, paths, trees and street furniture, and allow a vision of the scale of the original structure. Additionally, it would provide much needed shade to the park. Since so much of the ground of the former hippodrome is occupied, a trellis floating about 30 meters above would pass over the impediments below, and approximate the height of the former building. It would unify the area and become an attraction and point of discussion in its own right, a new entry in the tourist itinerary.

The site would be cleared of as many obstacles (trees, fences, light poles, etc.) as possible, allowing once again a view along the length of the spina. Necessary vehicle traffic would still follow the path of the old track, though calmed for the additional visitors using the park and viewing sphendome. Ideally the school on the sphendome would eventually be torn down (and added to the recycled park wall, of course), freeing up the privileged axial view of the Sea of Marmara from the city center.

The trellis would use an Ottoman motif (why not vine leaves?) for the screen, conflating multiple cultural histories in the new structure. The sun screen would employ ceramic technology, an industry that reached its high point in the Iznik tiles covering the Blue Mosque interior, and used today for everything from tourist plates to covering the space shuttle. At night, the ceramic screen could be lit from below, eliminating the need for the numerous pole fixtures, and during the day, it would glisten in the sun while giving shade. The goal would be to take advantage of the already existing Turkish ceramic industry, producing a scintillating, monumental structure that would provide highly practical sun protection.