Khlong Suan Luang lies between the heritage area of Rattakosin and the popular shopping area of Siam. It is fed by the Klong Saen Sab, the heavily used east-west canal connecting to the suburbs, and runs almost a mile until running underground and connecting to the Khlong Chong Nonsi in Silom. It runs parallel to the busy Banthat Thong Street, built in the early 1900’s only 60 feet to the east. The western bank has perpendicular alleys roughly every 100 feet. The edges are formed with sloped concrete, leading to water which is infrequently dredged. The base of the canal is permeable soil, allowing some water to leech back into the aquifer. Ad-hoc bridges are built every 50 feet or so. The Bangkok Department of Drainage and Sewerage which oversees the canals has done an admirable job of improving water quality, but they simply don’t have the resources to keep up with a rapidly growing, industrialized city that still often dumps waste directly into the water; Khlong Suan Luang has a powerful stench and unnaturally dark water with trash floating slowly by. Notably, the shop-houses lining the khlong were built in response to the roadway, and present their backs to the water. The strip between the canal and the building is used for cleaning, storage, and trash.

ASIDE: ELEVATED CITY

Bangkok is navigated on many overlapping levels. At the lowest point, the subway snakes 50 feet below grade; canals channel water just below the streets; most roadways are laid at grade; pedestrian walkovers are often the only means of crossing intense traffic; vehicle flyovers at busy intersections rise just enough to let traffic through; the Skytrain runs at the 4th floor of many apartments beside it; and new expressways arc over 100 feet in the air. Additionally, many of the malls around the shopping areas of Silom and Siam have elevated quasi-public plazas that abut the Skytrain or parking garages. It is the built manifestation of Ludwig Hilberseimer’s City Plan of 1927.

These elevated worlds are perhaps fortuitous as the city sinks several inches every year and the nearby ocean rises, increasing the possibility that Bangkok will again be a truly water-based settlement. Some day soon the current street level might lie abandoned, good only for exploring with scuba gear. Buildings and lobbies everywhere in Bangkok would begin on floor 2, causing confusion to visitors. A modern day Atlantis, the sunken world would disappear as the new city rises in layers over the tidal waters.

CANALS: ELEVATED VOYAGE

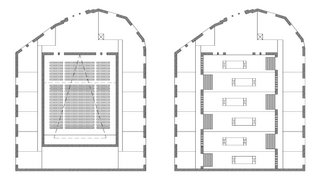

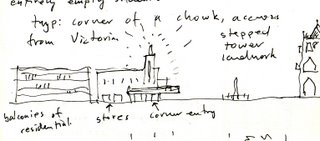

I propose an elevated canal over Khlong Suan Luang, a new level of infrastructure that acts as a demonstrative cleaning project and relaxed voyage through the city. It would follow the existing air-rights of the canal through several distinct parts of the city. The new canal would be a recreational experience for tourists and citizens, tapping into the desire for quiet, leisurely urban movement, an almost unheard-of phenomenon. It would signal a renewal of the characteristics that nostalgia seeks from village life, but updated for a modernizing and growing city. There are moments that approach this ideal, up on the pedestrian walkovers and Skytrain platforms where you can get up into the city and see it removed from the volume of traffic below. But even these are shared with the massive flow of people on their way to someplace else. A new viaduct would capture these moments but extrude them into paths. Thin boats would glide quietly on a fixed path and allow for hopping on and off. It would be an infrastructure that adapts the captured flow of a theme park ride and places it in one of the great environments in the world. Riders would literally drift through the city, experiencing it from a new perspective. The viaduct itself would be a machine for cleaning the water. Taking water from the canal terminus and returning it against the drainage flow to the source, the water would be cleansed in stages that would be linked with the stations: Sedimentation, Aeration, Biofiltration, Polishing and Integration.

Thus the canal would respond both to the surrounding urban context and the specific requirements of cleansing. The cleaner water would give the original Khlong Suan Luang new life below. The elevated canal would also effect the transformation of the built fabric above by giving the upper stories access to the viaduct. Currently, the shop-houses are appropriately aligned with the canal, but turn their backs to it in seeking to draw business from the roadway. The new elevated canal would tap into these blank facades for access and advertising potential. They would become 2-way shop-houses; the ground floor would service the roadway, and the third floor would service the elevated canal. Discrete bridges would reach out to passers-by and give local residents an opportunity to take advantage of the flow of riders. These bridges would act like old Thai canal entrance pavilions, allowing the boaters to choose whether to stop or not, rather than the street stalls that force pedestrians through a gauntlet on the sidewalk. The elevated canal would bring some of the comforts of driving a car (refuge and personal space), but would fold it into a new means of moving through the city. Future networks of elevated canals could traverse other neighborhoods in the city, ultimately linking up in a quiet network of water scrubbing machines.