The Regal, like many of the Art-Deco cinemas, is heritage listed. Its particular listing requires the exterior of the building to remain unchanged, while the interior and program can be renovated. The tendancy is for the cinemas to be gutted and converted into upscale shopping centers, taking some marginal advantage of the large open space. But retail has no problem finding an outlet in the city; it grows like kudzu, filling in leftover, forgotten and negotiated space. Can there be a profitable solution that revisits the quasi-civic and social role that cinema once fulfilled?

Cricket is officially more popular than Bollywood according to a recent Times of Bombay online poll: it was chosen 55% to 45% as the “new religion of India.” However questionable the methods, it is an indication of the rise of cricket. Within ten years it has gone from a gentlemen’s’ game among former colonies, to a $10 billion enterprise where cricketers rival movie stars in celebrity status. Recently the Indian national team, with Pepsi, has unveiled a new ad campaign starring mega movie star Shah Rukh Khan with the tagline “Join the blue billion,” a shocking reminder of the size of the fan base/market. However, as popularity for the sport has grown, the number of places to play has not.

In Bombay, the acceleration of population has led to a corresponding loss of open space. There is less than one square meter per person, compared with a recommended 16 sq. m/person. Most of this is found in the bundle of town greens called maidans in the old Fort area, only some of which are open to the public. Public gardens have extensive restrictions that rule out anything beyond walking and sitting. Elsewhere in the world the rise in urban population and lack of open space has meant a similar rise in urban sports. The ascendency of basketball as a world sport is only one signal of the shift from rural to urban. Thus it is not surprising to see the invention of indoor cricket, though still in its infancy, complete with a governing board and codified system of rules.

Bombay’s most widespread architectural feature is the verandah. Arguably a Hindi word in origin, verandahs were developed in the Indian subcontinent as a response to heavy monsoon rains and hot, humid summers. Indigenously they covered ground floor patio spaces but have evolved into any of the deep, semi-screened balconies that surround buildings. In the chawl multi-family housing typology it is also the means of circulation and primary socializing area. They are, in effect, like front yards. Laundry is hung, plants are put out, and little shrines are erected. Often each zone will be painted a different color to indicate ownership.

It is also where the line of cleanliness begins. In a city with little municipal cleaning, the public areas reach a neglected griminess that looks and smells of pollution, trash and sewage. But personal spaces, beginning at the verandahs, are spotless. Great care is taken in maintaining the order and aesthetics, since it is the most public aspect of the household. They are also the best place to watch street theater. The railings are just the right height to lean on and watch the crowds go by. Removed from the pressing flow, dirt and noise below, they offer a rare moment in the city where you can gain some perspicuity. Open to one side and “owned” by the other, they are simultaneously circulation, front yards, and opera boxes.

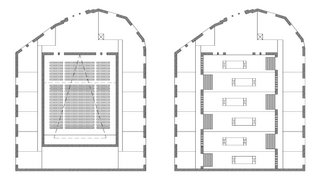

I propose a new hybrid cricket courtyard/courtyard housing typology. It would combine indoor cricket fields called pitches set in a courtyard surrounded by housing. The raked auditorium would be “terraced” into individual pitches and covered with turf and rented out by the hour. Ground floor retail would additionally be converted into pitches, allowing street views into the games. With a new glazed roof structure cricket can be played all year long, even during the four months of monsoons.

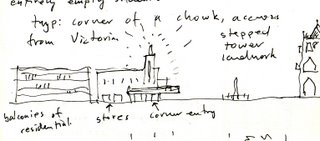

The existing housing would turn inwards for views of the light-filled courtyard, no longer at odds with isolation requirements of a movie theater. By carving up the acoustic shell around the auditorium, a new verandah would be created where there was previously an enclosed hallway. The verandah would overlook the games below; tenants would become figurative stewards of the courtyard. The residents would have access to the pitches during nighttime hours, thereby encouraging more ownership over the shared space. The existing lobby for the theater would become a cricket oriented leisure enterprise with food, drinks and a viewing area. Since it is already the public face of the building, it would retain its role in drawing people in and exhibiting the action.

1. Terrace the auditorium in coordination with the structure. Convert the terraces into rentable indoor cricket pitches with turf. The pitch can be closed during certain hours to allow residents access. It can be rented out for weddings and other events.

2. Preserve the existing facade and floor plates. Develop the lobby into cricket related leisure zone. Retain screen and projection booth for displaying games taking place inside; anyone can be a star! For important screenings of national team matches the terraces can be converted into a viewing hall.3. Punch through the auditorium shell, creating a verandah out of the existing hallway. Add stairways that act as seating for watching games.

4. Add color coded movable netting between pitches. Take advantage of Bombay’s newly relocated and modernized textile industry.

5. Replace opaque soundproof roof with transparent glazed courtyard structure. The courtyard can be used throughout the monsoon season.

Next Stop: Bangkok